Search the Community

Showing results for 'silver' in content posted by Jim Hemmingway.

-

Nice relics and older coins F350!!! That is a very good afternoon's hunt, and silver....especially old silver dating back to a time when Daniel Boone was settling in Kentucky... is always welcome. This made a very interesting read and your photos are excellent. 🙂 Thank you... Jim.

- 35 replies

-

- 2

-

-

-

- relic found

- relic detecting

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Nice description and photo about your most recent outing Jeff. Of course, you are familiar with an old saying that I view as an axiom......."when wheaties are here, silver is near". And it held true in this instance. 🙂 Congratulations on some quality recoveries!!! Jim.

-

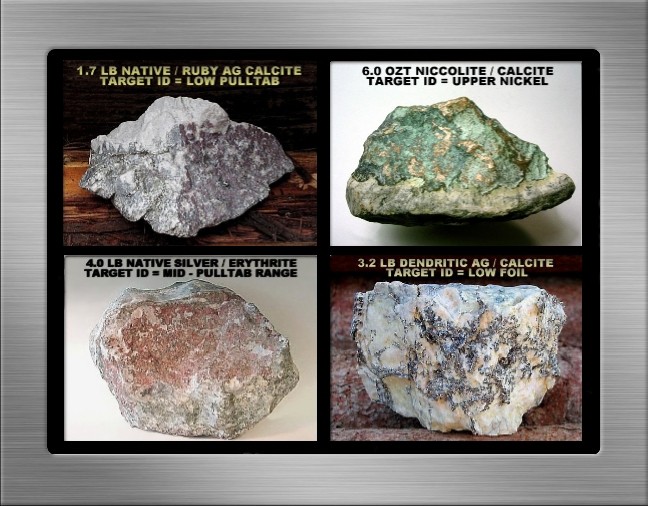

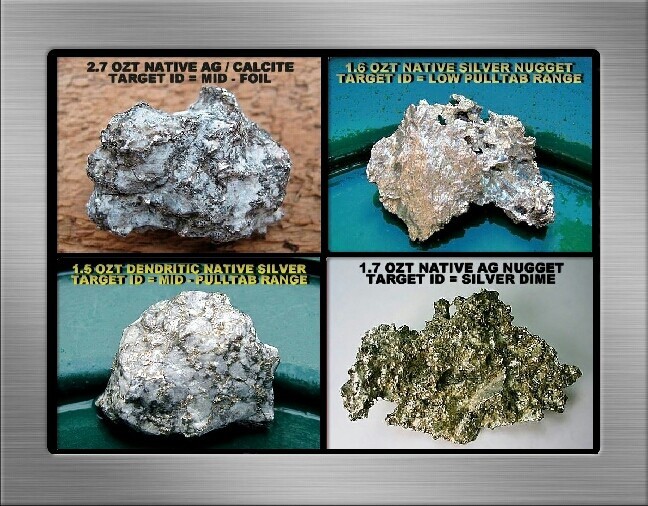

Collecting Native Silver & Related Minerals in Northeastern Ontario’s Silverfields Introduction… I’ve been cleaning and photographing some small native silver specimens that were found with a metal detector during my last few rockhounding visits to the silverfields of northeastern Ontario. They are commonplace examples of small silver that hobbyists can anticipate recovering from the tailing disposal areas of abandoned minesites, ranging in size from one-half to several troy ounces. The information and silver photos presented below may interest newcomers to the fascinating hobby of rock, gem and mineral collecting, particularly for those who have reasonable access to collecting sites for native silver and associated minerals such as the example displayed below. It is comprised primarily of rich, dendritic acanthite with some minor inclusions of native silver visible on the surface. Searching for Small Silver… When selecting an appropriate prospecting-capable metal detector for this application, consider the field conditions where you will be operating it. A large portion of your time will involve searching abandoned minesite tailing disposal areas because these sites offer you the best opportunity to find native silver and related minerals. (a) At many sites ferromagnetic susceptible substrates can be characterized as ranging from light to moderate, and will have little effect on a VLF detector’s ability to function effectively. But some areas, for example diabase dominant substrates, exhibit more elevated magnetic susceptibilities that to some extent will reduce a VLF metal detector’s detection depth and sensitivity, target ID accuracy, and discrimination reliability. The effects of harsh ground mineralization can be somewhat mitigated by operating a VLF metal detector in a true motion all-metal mode to maximize detection depth and sensitivity to targets. A smaller / DD coil will reduce the ground mineral footprint scanned by the detector, permitting the use of higher gain / sensitivity levels than would otherwise be possible. Regardless of target ID or the absence of it, ensure that all weak signals are investigated until the source is identified. An obvious alternative strategy to improve detection depth is to use a suitable PI detector for searching more difficult ferromagnetic ground mineral areas. A more recent Minelab PI model will ensure the best possible detection depth over such ground. (b) Consider the most frequent size of the silver you can expect to find with a metal detector. The small silver depicted in the accompanying photos is representative, and as noted above, range from about one-half to several troy ounces. They are typically larger coin-size targets detectable to very good depths, but keep in mind when choosing a suitable prospecting-capable VLF detector that most small silver is low conductive, and on average is characterized by a nickel target ID. (c) In some areas conductive pyrrhotite hotrocks are a real nuisance to both VLF and to PI detectors. Abundant pyrrhotite can render specific sites unsuitable for metal detecting. Target ID ranges from iron to low foil, with most pyrrhotite signals eliminated by upper iron range discrimination. My PI units, the Garrett Infinium and White’s TDI Pro, both generate enticing low conductive signals to solidly structured pyrrhotite, and similar to small, low conductive native silver, pyrrhotite PI signals must be dug. (d) Mining country, and abandoned mining camps in particular, are littered with iron trash of all sizes and description. Small, low conductive iron signals can be eliminated with suitable VLF iron range discrimination, but most non-descript small iron produces low conductive signals from my PI units. Similar to pyrrhotite, our PI units cannot reliably distinguish low conductive silver from low conductive ferrous trash. All low conductive PI signals therefore must be dug, and to do so is prudent fieldcraft regardless which PI brand or model is utilized for this detector-prospecting application. Incidentally, the same observation largely applies to VLF target ID reliability over deeper, weak target signals in more difficult ferromagnetic substrate conditions. Such signals tend to produce questionable readouts that either frequent or reside within the iron target ID range. To have any confidence in VLF target ID, it is necessary to remove surface material from deeper target signals until a reasonably strong VLF detection signal can be obtained. If any doubt about target ID remains, dig it to be absolutely certain of its identity. By comparison to low conductive iron, big compact iron such as larger drill bits and milling balls, and sizeable elongated iron such as broken pipes and implements, rail spikes, and drill rods tend to VLF target ID in the non-ferrous range. My PI units produce high conductive signals to large compact iron. A similar response, usually a double low-high or single low-high-low signal, is produced as the coil is swept lengthwise on elongated iron, whereas low conductive signals are normally produced when the coil is swept across the length of such targets. With native silver’s variable conductive potential (variations in size, shape, purity, structure) quite capable of producing both high and low conductive PI signals, the foregoing explains why all PI signals should be identified. While a large portion of our fieldwork in the northeastern Ontario silverfields is more suitably addressed with VLF units, we frequently use a ground-balancing PI unit for general scanning over tough ferromagnetic substrates where ferrous trash levels are tolerable. In these conditions we employ larger coils to improve detection depth over what VLF units can achieve. Additionally, our PI units eliminate or reduce most non-conductive iron-mineralized hotrock signals in the area. Such signals can be a particular nuisance when searching diabase dominant substrates with a VLF unit. Our VLF preference is to use mid-operating frequency range detectors for this application. Mid-frequency units respond reasonably well to both high and low conductive silver, and to weaker signals produced by low conductive particulate and sponge silver. By comparison to high frequency units such as my Goldbug2 for example, they are less vulnerable to elevated ferromagnetic mineralizations, and see both higher conductive targets and larger targets at better depths. Incidentally, low operating frequency units work reasonably well, but are less sensitive to low conductives. We operate both the mid-frequency White’s MXT and Fisher F75 for motion all-metal mode close-up scanning involved with removing surface material from hillslopes, trenching, sinking testholes, and for detecting excessively trashy areas requiring a discrimination mode, but there are other perfectly acceptable detectors that will perform well at these tasks. Your detector choice ideally should feature a target ID in a threshold-based motion all-metal mode, a discrimination mode, include a manually adjustable full range ground balance, a “fastgrab” ground balance for convenience and to assist with target signal evaluation, and a selection of searchcoil types and sizes. Which type of metal detector is best suited for this application? We operate the PI and VLF units described above to deal with variable field conditions and objectives, but the VLFs do much of the fieldwork here. Newcomers should begin with a VLF unit that incorporates the features outlined above as a minimum. You may wish to supplement your stock coil with larger and smaller coils to increase your versatility in the field. Once you have gained some field experience with the conditions as described above, and generally have learned more about collecting silver minerals, you can make a more informed decision as to whether acquiring a suitable prospecting-capable PI unit is a viable choice to satisfy your objectives in the field. Where to Look for Silver & Other Minerals… As a general principle regardless of the type of minerals one seeks, successful collecting invariably depends on knowing where to look and a willingness to do serious pick and shovel work. Surprisingly detailed information about where to search for many minerals is readily available online to hobby newcomers, with many collecting sites readily accessible by personal vehicle. On occasion, more remote sites or identified prospects will typically require a short hike. For example, extensive information about abandoned gold and silver mines can be accessed online, and many current government publications are available to interested hobbyists. My personal favorites include a series entitled Rocks and Minerals for the Collector authored by Ann P. Sabrina, in association with the Geological Survey of Canada. These publications supply practical, useful information pertaining to abandoned minesites throughout Canada. They provide road guides to accessible collecting locations, a brief history of a site’s mining operations, normally include production numbers for more prominent minerals such as cobalt, lead, zinc, nickel, copper, silver and gold, and usually provide a comprehensive list of mineral occurrences for each site. For casual or recreational prospecting enthusiasts visiting this area with limited time to search for silver ores and nuggets, select abandoned sites that will more likely produce detectable native silver based on past production numbers. You can detect these sites with the certain knowledge that highgrade silver was inadvertently discarded to the tailing disposal and nearby areas, sometimes in considerable quantity. The probability of successfully recovering specimen grade silver is sharply improved compared to searching for outback silver float, obscure prospects, or low production sites. To improve the likelihood of finding silver, try to identify areas where valuable silver was handled and transported. For example, look for evidence of surface veins, shafts, and storage areas where silver was graded, moved, and sometimes inadvertently misplaced. There are many plainly visible field indications of former mine buildings, mill sites, ore transport routes and abandoned trails. While quantities of silver were frequently discarded to tailing disposal areas, keep in mind that some highgrade silver was unknowingly included with waste rock for road and other construction projects. Hobbyists have also detected large specimen grade silver that was occasionally lost to spills on steep embankments, washouts, or sharp bends along the transport routes of the time. Incidentally, we occasionally see examples of careless or halfhearted retrieval techniques when only a few more inches of digging in tough ground would have unearthed quality silver that produced unmistakably solid, tight non-ferrous target signals that could not be mistaken for iron trash. A general suggestion to newcomers is to be thorough in all aspects of your fieldwork, examine abandoned digsites, and dig all questionable target signals until the target is identified. Briefly About Acanthite… As a related but slight diversion from the topic of searching for small native silver, depicted below is a small but massively structured example of acanthite / native silver recovered from the Kerr Lake area of northeastern Ontario. While selecting some reasonably photogenic small silver examples, I decided to include it here because valuable acanthite https://www.minfind.com/minsearch-10.html recoveries are a rather infrequent occurrence in my personal experience and therefore welcome additions to my collection. After some 30+ prospecting seasons, I’ve never detected acanthite as a stand-alone mineral. My acanthite finds have always contained some detectable native silver. For those unfamiliar with this mineral, acanthite is a dark silver sulfide (Ag2S) approximately comprised of 87% silver and 13% sulfur. Smithsonian Rocks & Minerals describe it as the most important ore of silver. Much of the world’s current silver demand is satisfied as a by-product from the refining of argentiferous (silver-bearing) galena. Galena, a lead sulfide, generally contains some small (< 1%) amount of silver in the form of microscopic acanthite inclusions as an impurity. Acanthite is occasionally misidentified as argentite by hobbyists, but the correct mineral classification when referring to silver sulfide (Ag2S) at room temperatures is acanthite. Both these silver minerals possess the same chemistry but different crystalline structures. Argentite forms in the cubic (aka isometric) system at temperatures above 177 degrees Centigrade (temperature slightly varies according to reference source). Below that temperature acanthite is the stable form of silver sulfide, and crystallizes in the monoclinic system (Smithsonian Rocks & Minerals 2012 American Edition, Eyewitness Rocks & Minerals 1992 American Edition, Wikipedia). The transformation of argentite to acanthite at lower temperatures often distorts the crystals to unrecognizable shapes, but some retain an overall cubic crystalline shape. Such crystals are called pseudomorphs (false shapes) because they are actually acanthite crystals in the shape of argentite crystals. Acanthite crystals frequently group together to form attractive dendritic (branching) structures embedded in light-hued carbonate rocks that range from rather intricate to massive. In the field, try to be visually alert to darker (typically sooty-black) acanthite that may be exposed while digging targets, trenching, or by chance encounters with recently exposed material. For example, the local township occasionally removes tons of tailings for road and other construction projects, resulting in fresh new surfaces for hobbyists to explore. Prominent Minerals Associated with Native Silver… Native silver, acanthite, pyrargyrite and proustite ruby silvers, stephanite, and other collectable silver minerals primarily occur in carbonate veins in association with gangue minerals such as quartz, chlorite, fluorite, barite, albite, hematite, magnetite and many other minerals related to relatively shallow epithermal deposits. Attractively structured native silver embedded in light-hued carbonates, or for example in association with other silver minerals such as acanthite and proustite, is highly valued by the mineral collecting community. For newcomers incidentally, structure refers to how the silver is formed, examples include massive or nuggety formations, plate, disseminate or particulate, sponge, highly crystalline, and various dendritic or branching patterns as illustrated by the native silver example in the multi-photo below. The native silver in this area is intimately associated with major cobalt-nickel arsenide deposits that include notables or collectibles such as safflorite, cobaltite, nickeline, and skutterudite. A number of these ores, typically arsenides and sulfides, produce perfectly good signals from VLF metal detectors. Solidly structured nickeline (aka niccolite), a nickel arsenide, is a fine example that can generate strong signals from both VLF and PI metal detectors. Moreover, it is not unusual for rockhounders to find surface examples of nickeline with its copper-green surface oxidation annabergite, and cobaltite displaying its pink-to-more infrequent reddish surface oxidation erythrite as depicted below. A wide variety of additional minerals can be collected from the mine dumps. These include more localized occurrences, for example, allargentum (silver antimonide), titanite (wedge-shaped, vitreous calcium titanium silicate formerly called sphene), native bismuth, chrysotile serpentine (asbestos), rutile (titanium oxide) and breithauptite (nickel antimonide), to more commonplace minerals such as sphalerite, arsenopyrite, chalcopyrite, bornite, galena, marcasite, iron pyrite, and so forth. A Final Word… In closing we should point out to interested readers that there has been a resurgence in active exploration for both diamonds and cobaltite minerals in the northeastern Ontario silverfields. The existence of diamonds has been widely known for years, and historically there has been a strong industrial demand for cobaltite for hardening steels and other alloys, paint, ceramic, and glass pigmentation, and in other various chemical manufacturing processes. Apparently now there is increased interest in cobaltite for the manufacture of batteries. Industrial demand notwithstanding, for many years cobaltite has also attracted hobbyists interested in recovering valuable crystals. I hope that both experienced mineral collectors and hobby newcomers have enjoyed reading about native silver and a few of the more prominent associated minerals in this area. Thanks for spending some time here, good luck with your rock and mineral collecting adventures, perhaps one day it will be our good luck to meet you in the field. Jim Hemmingway, October, 2019

-

Abandoned Trails in Silver Country Introduction… Silver country represents a small part of a vast, heavily forested wilderness perched on the sprawling Precambrian Shield here in northeastern Ontario. Away from the small towns and villages, and widely scattered farms and rural homesteads, there exists a largely uninterrupted way of life in the more remote areas. There are uncounted miles of lonely country backroads, overgrown tracks leading to abandoned mining camps, innumerable rough timber lanes, and a virtually infinite tangle of winding trails that reach deeply into the distant forests. Nothing in my experience has been so completely companionable as the soft forest whisperings and the beckoning solitude that reigns over this ruggedly beautiful country. This is where my carefree days of autumn prospecting have been agreeably spent for many years. We returned again this year to unbounded, satisfying autumn days of kicking rocks, exploring and detector-prospecting adventures, followed by evenings spent evaluating silver ores while savoring hot coffee over blazing campfires. Irrespective of silver recoveries, the flaming autumn colors of the boreal forest are the real treasure of the season. They persist for only a few short weeks, reluctantly yielding to the autumnal yellows of the tamarack, birch, and aspen in sharp contrast to the deep conifer greens. Scenery as depicted below accentuates your enthusiasm to get into the field, and pretty much ensures that an autumn prospecting trip to silver country is a memorable experience. General Discussion… Unprecedented, persistently wet conditions eliminated any potential for a banner season, but nonetheless we did manage to find considerable worthwhile silver. In addition to an assortment of rich silver and associated minerals, my friend and occasional partner Sheldon Ward recovered a large, very high conductive native silver ore that we’ll take a closer look at shortly. Most of my quality silver finds were fairly small, although a specimen grade silver ore at five pounds was found during the final week of the trip, and frankly I felt very fortunate to get it. Larger material was recovered, for example a 24-pound highgrade silver ore from the same area, but these invariably were mixed ores co-dominated by cobalt and various arsenides, most notably niccolite as illustrated below. On a more positive note, we both found plentiful small silver generally ranging between one-half and ten ounces that added real weight to the orebag over the season’s duration. It is much easier to find small but rich, high character silver than is the case with larger material. Even so, specimen grade detectable silver in any size range is becoming increasingly difficult to find at many of the obvious, readily accessible sites nowadays. The photo below is a pretty fair representation of the overall quality, although anything below a half-oz was excluded from this shot… such are not terribly photogenic beside larger samples. Some rich ‘nuggety’ ores were HCl acid-bathed to free the silver from carbonate rock, and all samples were subjected to a rotary tool circular wire brush to remove surface residues, followed by a dish detergent wash and rinse. By way of a brief background explanation to readers unfamiliar with this prospecting application, we search for more valuable coin-size and larger pieces of silver. Natural native silver target ID is determined by physical and chemical factors such as silver purity, types of mineral inclusions, structure (for example, dendritic, plate, disseminate or particulate, sponge, nuggety or massive), size, shape, and the profile presented to the coil. Virtually all natural silver from this area will target ID from low foil up to a maximum of silver dime range. Only infrequently over the years have we found isolated, rare examples of our naturally occurring silver exceeding that range. The specimen depicted below is a commonplace example of silver typically recovered here. It isn’t terribly large or particularly handsome, but it is mostly comprised of native silver by weight. Its target ID is a bit elevated from the usual, but consider that even small changes to some of the more influential factors listed above can significantly alter target ID. I tend to pay minimal attention to it when evaluating samples. It was detected adjacent to an abandoned mining track that leads directly to a former mill site at the mining camp scene depicted above. No treatment required other than a leather glove rubdown followed by a soapy wash and rinse, in fact it looked quite presentable fresh out of the dirt. The darker material you see is heavily tarnished native silver that I intend to leave undisturbed. Ground conditions also play an important role in determining target ID, and refer to factors such as the strength of non-conductive magnetic susceptible iron minerals present, ground moisture content, proximity of adjacent targets, and disturbed ground. These factors sometimes contribute to good silver at depth producing a VLF target ID within the iron range. Probably the best photo example available to me is a specimen found a few years back at good depth in tough magnetic susceptible diabase. It produced a predominantly iron target ID on the Fisher F75. It was detected in a fairly low trash area, the signal was suspect, and it was checked with the groundgrab feature. In this instance, there was no ground phase reduction to more conductive values as would be anticipated over rusty iron or a positive hotrock, and so the target was dug. The general rule of thumb over questionable weaker signals, regardless of groundgrab results, is to remove some material to acquire a stronger signal and target ID readout before making a decision to continue digging in our difficult, hard-packed rocky substrates, or to move on. If there is the least doubt, we dig the target to learn what actually produced the signal. The specimen depicted below was found by eyesight while hiking along an old abandoned rail track. In the field our rock samples seem more attractive or valuable than they do once we return to camp, where we tend to view them far more critically. If they don’t look to have good specimen grade potential, my samples are either abandoned in an obvious place for others to find, or given away to visitors back at camp. But that’s just me, most hobbyists are more resourceful with unwanted samples, they’re refined by some, subjected to treatments, or slabbed, and ultimately sold. In any case, this rock didn’t terribly impress me and was placed with other discards on the picnic table. But nobody other than my wife seemed much interested in it, and that is how it came to be included here. In its original condition, it could only be described as nondescript, with very little showing on the surface prior to treatment. It did produce a broad solid PI signal, despite that the few surface indicators were non-conductive dark ruby silver pyrargyrite and to a much lesser extent what I suspect is the black silver sulfosalt stephanite. To see more, it was acid-washed to expose silver and associated minerals, cleaned-up with a rotary tool, followed by a dish detergent bath and clean water rinse. Both these minerals produce a good luster that makes them a bit more difficult to distinguish from native silver in a photo. But in reality it is easy to see the differences and do some simple tests to confirm if necessary. The acid treatment revealed that the sample does have a good showing of dendritic native silver, a timely reminder that metal detectors see what we initially can’t see inside rocks. Abandoned Trails, Minesite Tracks and Roadbeds… Abandoned, frequently overgrown trails, mining tracks, and roadbeds provide convenient routes to prime detecting sites that otherwise would be much more difficult to access. But the important thing is that most such routes were built with discarded mine tailings to considerable depth, and contain good silver more frequently than you might think possible. Some snake through the bush to more remote areas, but the vast majority of these now abandoned routes were built to service existing minesites at the time. They were used to transport discarded rock to the tailing disposal areas, and silver ores to storage buildings and to mill sites, and generally to service other mining camp requirements. We know from research and experience that silver was misgraded, inadvertently misplaced, or lost directly from spills to eventually reside on, within, or alongside these now abandoned trails and roadbeds. These mine tailings… frequently containing rich silver… were also used to build storage beds, minesite entrances, loading ramps, and as noted… routes to facilitate waste rock transport. All these offer excellent, obvious prospects to search with a suitable metal detector. The nugget below, with several other pieces, was found in the tailings adjacent to the abandoned track in the photo above. Some good weather following a horrendous week of persistent heavy rainfalls prompted me to head out late one afternoon for some casual detecting. I had sampled those tailings earlier in the season but nothing by way of thorough searching. And while the silver was generally small, it had been surprisingly good quality. So I was looking forward to a few relaxing hours of detecting… nothing ambitious that late in the day… just happy to get out of camp. That particular spot formerly housed silver storage beds, and was now replete with large rusty nails. I should have used a VLF unit, as things would have gone much more quickly. VLF motion all-metal detection depth in that moderate ferromagnetic substrate would pretty well match Infinium equipped with the 8” mono, with the further advantage of target ID and groundgrab features to assist with signal evaluation. If conductive pyrrhotite hotrocks had also been present, I would have switched over to my F75 or MXT to take advantage of target ID. But I stayed with the Infinium primarily because I enjoy using it. By comparison it is slow going, but that isn’t such a bad thing over potentially good ground. It silences what can be described as VLF ground noise, in addition to sizable non-conductive mafic hotrocks in this area. It also has some limited high conductive iron handling capability, for example elongated iron such as drillrods or rail spikes at depth that VLF units using iron discrimination modes misidentify with perfectly good signals and non-ferrous target ID readouts. More information on this subject can be found at… http://forum.treasurenet.com/index.php/topic,384975.0.html http://forum.treasurenet.com/index.php/topic,385640.0.html Nearly all the signals proved to be nails, plus one drillrod with a perpendicular profile to the coil. The silver below produced a low-high signal in zero discrimination and a good high-low signal in reverse discrimination (maximum available pulse delay setting) at maybe eight to ten inches depth. The exposed silver was unusually tarnished and the remainder partially embedded in carbonate rock. It was acid-bathed to free the silver, cleaned with a rotary tool silicon carbide bit and circular wire brush, followed by a detergent wash and rinse. While searching one such abandoned route with his Fisher F75 equipped with the stock 11” DD elliptical coil, Sheldon Ward found a large highgrade silver ore comprised of a thick calcite vein containing massive dendritic native silver. The vein material weighs about 25 lbs, and was attached to a mafic host rock. It generated a moderate but broad signal from several feet depth, requiring an hour of hard pick and shovel work to recover it. It possesses an unusually elevated target ID in the silver quarter range. After 30+ years searching this area recovering numerous silver ores and nuggets, I've seen only a small handful of silver produce a similar target ID. On site we obviously have the benefit of closely examining the vein material, but it’s more difficult for readers to evaluate the silver based on photos only. Outdoor photos do tend to make native silver look much like grey rock, and unfortunately this one is smudged with dirt. I’ve added an indoor photo from Sheldon that displays the vein material after it was separated from the host rock and cleaned. Sheldon if you happen to be reading along here, congratulations on your many superb silver and associated mineral recoveries over the past year. Nothing that your dedication and persistence achieves in the years to come will ever surprise me. WTG!!! Persistence Pays Dividends… Let’s wrap things up with a tale about the rock sample below. It was recovered at the edge of a tangled overgrown trail near a former millsite just a few years ago. Its recovery exemplifies that the more you work towards your objective of finding silver or gold, the more likely your probability of success will correspondingly improve. I’d been searching that particular area for two days without meaningful results while evaluating a newly purchased Garrett Infinium for this application. The second day had again been filled with digging hard-packed rocky substrates for iron junk, worthless or otherwise unwanted arsenides, and plenty of conductive pyrrhotite hotrocks. As the sun was reaching for the western horizon, I decided to make one final effort before heading elsewhere the following day. Methodically working along the old track towards the mill, lots of old diggings were plainly visible. But previous hunters had ignored an area with a scattering of large, flat rusty iron pieces and other miscellaneous modern trash. I moved quickly to clear it away, because daylight was fading fast beneath the dense forest canopy. My Infinium soon produced a surprisingly strong high-low signal that practically vanished in reverse discrimination… a promising indication of naturally occurring ores. I dug down a foot before my Propointer could locate the signal. Probability says that it could have been any number of possible targets altogether more likely than good silver. But fickle Lady Luck was more kindly disposed towards me that evening. The rich, finely dendritic piece depicted below was in my gloved hands just as twilight was stealing across that lonely abandoned trail in remote silver country. A Final Word… A special mention to my friend Dr. Jim Eckert. I hadn’t seen much of Jim recently, but happened across his trail late one overcast afternoon in the outback. I was about to hike into a site when this fellow came flying down the trail on a motorbike, and despite the riding helmet I recognized him. We had a good long chat about this and that… Later in the season, one bright sunny afternoon at the site of my short-lived testhole diggings, Jim stopped around to show me a recent specimen find comprised of native silver and crystalline stephanite. We talked mineralogy and other interests many hours until finally the sun was going down. These were highlights of the trip, and I want to say how much I enjoyed and appreciated having that companionable time together. Thanks to everyone for dropping by. We hope that you enjoy presentations about naturally occurring native silver, particularly since it is different from what many rockhunters normally encounter in their areas. All the very best with your prospecting adventures… perhaps one day it will be our good luck to meet you in the field…………………… Jim. Reposted July 2018 Detector Prospector “Rocks, Minerals & Gems”

-

What's The Largest Item You Have Dug????

Jim Hemmingway replied to dogodog's topic in Metal Detecting For Coins & Relics

Hi dogodog… an interesting topic, with some unusual recoveries described below. For several decades now, our autumns have been occupied with prospecting for native silver and other commonplace minerals throughout northeastern Ontario. A few years ago, I found a specimen grade 101-lb native silver-calcite ore while metal detecting with a Fisher F75 metal detector equipped with a standard 11-inch DD coil. I almost ignored the shallow, blaring signal, initially thinking it would probably be shallow rusted ferrous sheeting or a very large pipe or implement. However the target ID and fastgrab readouts did not indicate ferrous material, so the signal was dug. The result provided me a few exciting moments as can be imagined. I was never so pleased when finally I got it out of the bush and into my truck. I don’t have a decent photo of it, mainly because it is about two feet in length, and nearly impossible to get close enough to properly identify what is silver and what is calcite. But I’ll post what I have, and include a “group” photo that includes a few other larger finds, plus a close-up shot depicted further below that allows the reader to see the silver in good detail. The ‘close-up’ photo below provides a better look at the silver by using my older camera’s optical zoom feature. The rock is inundated with thick coarse silver that protrudes from about an inch on down to the tiniest veinlets and horns. The vein material travels completely through and around the rock. Other than one narrow section on the reverse side, there is nowhere to place your finger without it resting on silver. Checking it with a multimeter, there are no pair of silver contacts on this rock that are not electrically connected. Thanks again for an interesting topic…. Jim. -

Excellent results Norm, congratulations are certainly in order!!! Many coin hunters consider it an axiom that when wheaties are here then silver is near. Good luck with any further detecting excursions to that site....... Jim.

-

Beautiful silver finds Againstmywill!!! The ring is rather ornate and obviously in very good condition too, but the first item tugged at my heartstrings because it reminds me of a song we once sang to our children when they were infants as we danced with them around the dining room... ZOOM ZOOM ZOOM we're going to the moon, If you want to make this trip... Climb aboard my rocket ship, ZOOM ZOOM ZOOM we're going to the moon!!! Thanks for sharing with us............ Jim.

-

Hi Bear... thanks for dropping by with your comments, most kind of you to do so!!! I wish that I could provide a placer silver photo, but unfortunately in this area our metalliferous silver recoveries are in the form of float silver or hardrock native silver. As a substitution, below is a photo of a rather plain silver nugget. It's not ideal of course, but it is about as close as I can provide at the moment. Hopefully you might be able to find some in your area that would undoubtedly interest many readers. All the very best, and good hunting!!! Jim.

-

Hi Glenn... thanks for your comments, its nice to have this opportunity to speak with you!!! Taking your last question first Glenn, yes this area produces fine examples of wire silver. I might add that wire silver is often in close association with acanthite. I have not enjoyed much luck with finding it in any appreciable size, but have seen many examples from friends in the area, such as the one below compliments of Dr. Jim Eckert. Below are some examples of dendritic silver, including an enlargement of the dendritic silver example portrayed in the article's multi-photo because it illustrates dendritic structure quite well. The others serve as additional examples, the outstanding "fern" silver slab is from the personal collection of Dr. Jim Eckert with thanks....................... Jim.

-

Hi Bob... thanks...so pleased to hear from you!!! Your comments are most kind. I don't know how much more silver hunting we'll accomplish for awhile. As you know, my interests have been leaning more to to non-metallic minerals in the renowned Bancroft vicinity. In fact we're heading north (hopefully) sometime later this week. I'd like to find some larger examples of tremolite, apatite, and titanite that will take a decent photo. With any luck and some determined fieldwork, I think we might be able to produce a different type of article later in the season. Over the interim, I hope that you will be able to post a little about your pursuits this past season, there is no doubt that others would enjoy viewing some of your mineral recoveries. Trust you had a good season, and that all is well with you and the family.......................... Jim.

-

Simon... we've always realized how very fortunate we have been to reside within reasonably accessible distance to northeastern Ontario's silverfields. A wonderful opportunity to fill our lives with countless adventures, and we enjoyed every moment there. Below are two more examples of silver minerals, in keeping with the thread topic. Both happen to be white backgrounds because we've learned that it depicts native silver and acanthite nearly as realistically as these samples appear on my shelves. As to size, the acanthite dominant sample immediately below is about equal to a large man's fist, perhaps a bit larger.................... Jim.

-

Thanks Simon... for those kind words of encouragement. We should keep in mind that silver in this area is normally quite large compared to gold, with recoveries generally ranging from several ounces to multiple pounds. This factor permits us to use our older, modestly deepseeking PI units with reasonable success because our larger silver can be detected to much greater depths. .................. Jim.

-

Water Detecting At Beaches With No Tide

Jim Hemmingway replied to Brian's topic in Metal Detecting For Jewelry

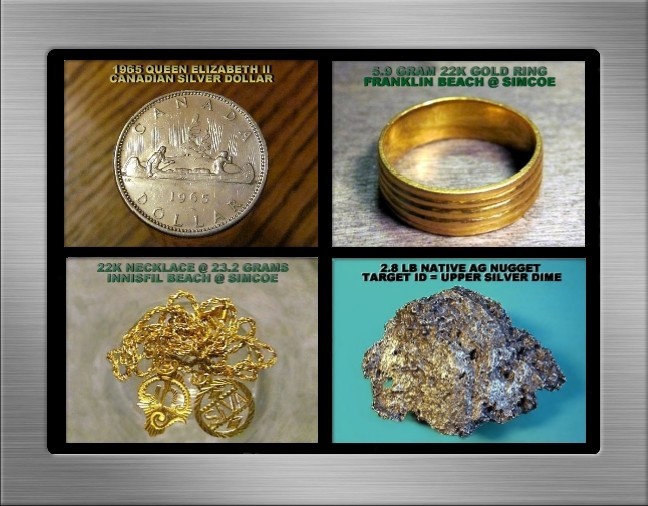

Hi Brian… and welcome to the forum!!! In addition to "no tide" you didn’t mention whether you are anticipating detecting small freshwater lakes with little or no wave action or larger lakes with wave action. So I’ll address both scenarios to supplement what has already been said above. Success at the small lakes will depend on day-use bather numbers and on the type of bottom substrate. The bottom substrate could range from a hard clay or hardpack gravel bottom that will hold targets, to some combination of soft mud, silt and sand mixture that allows targets to quickly sink out of detection range. If the latter, and bather usage is reasonably high, you may need to detect these on a regular basis while the targets are still detectable. Try these sites and your experience will dictate whether they are worth your time and effort. Many freshwater pond and river “swimholes” have been around a long time, and may or not see much present day usage. It could very well be a case of cleaning it out on a one-time basis and moving on to other productive sites. Again, your on-site experience will help you with that decision. We search generally larger lakes here in Ontario, that do have good wave action as a result of the prevailing winds and of course from summer heat that develops on-shore breezes. These factors facilitate the creation of a series of sandbank-trough-sandbank-troughs in the lakeshore shallows, sometimes extending out to shoulder depth, but that also conveniently run parallel to the shoreline. The sandbanks tend to be hardpacked such that small rings remain detectable for several days to several weeks, whereas coins and tokens typically remain within detection range for a much longer duration. The troughs are normally clay-gravel hardpack swept clean by water action, hence all targets remain detectable for many years subject of course to any sandbar movement over extended periods of time. We hunt these troughs routinely because they’re wonderfully productive for gold and silver jewelry at high day-use beaches, and incidentally freshwater is much less aggressive with silver coins and jewelry than saltwater. Even nickels lost nearly a century ago surface looking quite presentable as per the photo below. Most of my jewelry finds are recovered in knee-to-shoulder deep water. Lakies’ rings are more commonly found in shallow waters due to playing with their small children. Men’s rings are much more widely distributed. Sandbanks and the shallows are areas for throwing beachballs and frisbees, and other horseplay. The bottom substrate can play a role too, for example if there are rocky formations near or at the shoreline at a popular beach, those rocks are magnets for men’s wedding bands. Now just a word of caution. Stay alert to small storm drains and creeks entering unfamiliar beach areas where you search. Summer flows normally are quite low or non-existent, but immediately after storms or in the early spring these discharge points can be raging torrents that over many years may have hollowed-out quite a steeply-banked underwater channel running out into the lake. Perhaps no issue for bathers, but for a detectorist loaded-up with gear the channel slopes can trap and pull you quickly into deep water. Water hunting for coins and jewelry as pictured below can be very rewarding particularly if you have access to countless inviting freshwater beaches that exist here in Ontario. But all you need is one good, productive beach that gets a lot of day use bathers and you can return at regular intervals and do quite well. Good luck Brian, and please don’t forget to post about your adventures to this forum..................... Jim. -

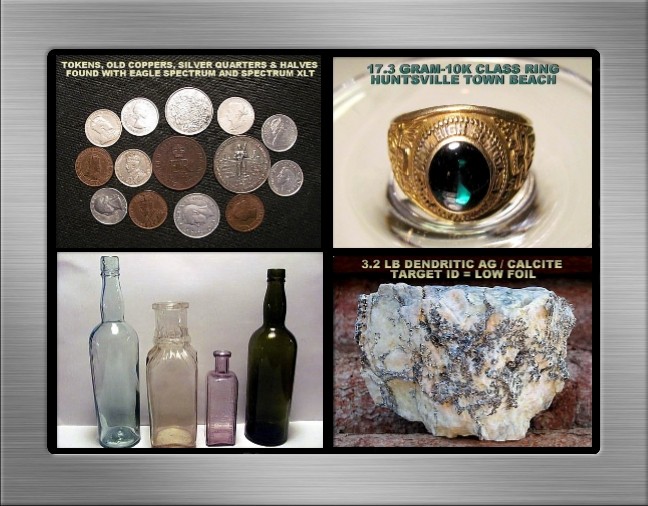

Hi Gerry… I’m glad that you mentioned utilizing the depth meter. I was tempted to earlier, but decided not to venture too far away from your initial thread topic. Once I’ve isolated a signal the first order of business is to precisely pinpoint, carefully measure the target depth, and then evaluate the target signal. That information enables me to decide whether or not to dig it!!! The depth meter generally has a major impact on decision-making for most areas and most target ID range targets. I search for deeper silver coins as a rule of thumb, but not always. If the signal is shallow but reads penny / dime range I dig it in hopes of a silver ring, pendant or an infrequent bracelet. There are so many potentially productive coin-hunting sites that it is not rational or even possible to dig every coin signal, particularly not shallow coin signals. Nowadays in Ontario those shallow signals are mostly comprised of iron and not worth digging. By comparison, when hunting impermeable clay dominant substrates where coins don’t settle deeply, the depth meter really has little or no value. The older parks and picnic areas with high clay content soils in Toronto normally produce silver at very shallow depths. As noted previously, I tend to dig all signals in the screwcap range because silver jewelry can be had at any depth. Again this strategy is tempered by the soil conditions, insofar as targets will quickly drop out of detection range in dark moist soils characterized by a higher detritus content. In such conditions, the depth meter comes to the fore. Men’s gold rings are much more common within the extended pulltab range. One has to be circumspect about where we pursue these signals. Well groomed city parks and picnic areas that feature extensive gardens are productive places to hunt, as are sports fields, volleyball courts, baseball outfields, relaxation areas adjacent to tennis courts, and so forth. The depth meter is as important here as it is for the silver coin range because we wish to focus on the deeper targets, presuming that heavier gold will sink beyond lighter aluminum targets more quickly over time. Again, you’ve got to be selective primarily based on target depth, because you cannot afford the time to dig it all. I used the same strategy with the foil and nickel ranges but never realized much success for the time / effort. It produced quantities of foil of every description, nickels, costume jewelry, and a few thin gold rings that barely warranted digging in well-groomed, upscale neighborhood city parks. Responsible detectorists must be selective about where and how often to dig in such environs, or risk eviction by park staff. Mind you, I did recover two handsome ladies diamond rings (one 18K with a modest .35 carat diamond in a platinum setting now resides in the wife’s jewelry box), so I shouldn’t complain too much I suppose. Eventually I abandoned hunting gold on land and turned to water hunting for better results. That decision dramatically increased the gold finds for the time and effort spent doing so. I do enjoy the environs and the rewards, but for me water detecting is a crushing bore compared to prospecting or coin hunting. A few months ago I mentioned to you that central Ontario has countless, high usage beach / swimming areas. Within a few hours of my home in central Ontario, there are numerous such sites available to water hunters. Yearly gold renewal has improved because there has been an increase in 22K jewelry recovered at sites closer to Toronto, primarily Lake Simcoe beaches. Nowadays I search Lake Simcoe’s eastern beaches because these see intensive day use from Toronto and nearby large population centers. Moreover the prevailing westerly winds have created extensive troughs between the sandbanks that run parallel to the shoreline. Gold lost in these “collection” troughs is much easier to visually locate, and this is true even using a headlamp at night. Targets can easily be cleanly scooped from the relatively sandless, smooth hard bottoms. There is no need to concern myself with target ID or depths out in the water. I dig it all. With early retirement, lately I’ve focused more on prospecting for native silver. It combines a natural interest in the northern wilds with that of detecting potentially valuable silver. I also thoroughly enjoy mineralogy generally, and eastern Ontario possesses a spectacular mining history and terrific mineral diversity, particularly the famous Bancroft areas. One of the few places globally where a mineral explorer can find and recover specimen grade fluor-richterite. As recently as a trip to the lower Algonquin area early last December 2018, I held a softball size, handsome museum quality specimen in my trembling but eager hands. Well no I didn’t actually find it in the deep, forbidding winter snows, but providentially the general store had several on display!!! And a nicely provisioned snack bar too!!! Almost forgot to comment on the beautiful class ring that you posted above. An unusual looking piece, you invariably post interesting and sometimes extraordinary items. WTG on digging that signal, most impressive given the circumstances. The photo below leaves no doubt about my metal detecting interests… ..........Jim.

-

Hi Gerry… I don’t own an Equinox but I think that you’re also asking what sort of items we normally expect to find if we dig signals that target ID generally in the screwcap range. That is to say the target ID range that lies between upper pulltab and zinc penny range. I dig all targets in the screwcap range because there are many unpredictable, interesting or unusual items within that conductive range. That’s not to say that we don’t find our share of trash such as aluminum junk and discarded screwcaps, costume jewelry including cheap plated rings, infrequent broken watches, knives and utensils, all damaged to some extent from years of exposure to ground moisture in concert with various soil chemistries. On the other hand, this target ID range produces commemorative tokens, the large Victoria, Edward VII and George V Canada One Cent coins, and our silver half-dimes. It also produces a variety of generally smaller sterling silver jewelry such as small silver rings, pendants and charms. We occasionally detect larger silver rings that fall into screwcap range because they have become disconnected where originally sized to one’s finger. Of course other valuables such as gold rings do occasionally surface, but these are a far more rare occurrence in that particular target ID range. I’ve doubtless not mentioned many other items that fit into the screwcap range. Thanks for a nifty, interesting thread Gerry.

-

True Value Of A Coin. Whats Your Take?

Jim Hemmingway replied to Gerry in Idaho's topic in Metal Detecting For Coins & Relics

Hello Gerry… I completely agree with you, and especially so to the idea that very frequently how we assign a value to a recovered item is based on many possible facets that may totally exclude any monetary value consideration. You were motivated by a wish to share both your coin and the experience involved with finding it with your Dad, and to subsequently enter your club’s monthly finds contest. I might add that there had to be a very real sense of accomplishment, and that to me is one of the essentials that keep many of us interested in the hobby. That aside, it was an extraordinary find, involved a wonderful story, and you deserve all the credit in the world. The most important consideration for many of us has to be what you feel a recovered item is worth to you. As you’ve stated above, when you don’t need the money, it doesn’t mean as much or anything to you. It may therefore be very difficult to assign a monetary value because an item may appeal to us for many other reasons as noted above. We may feel that the probability of finding another such item of similar age or condition is highly unlikely. Older coins, particularly silver coins may appeal to us aesthetically and / or for reasons of historical interest. Other more practical considerations that might factor into the equation may include the time invested, personal expense, travel involved, effort with searching multiple sites, motivating oneself to do the research and get into the field, and the fieldcraft (and luck) that ultimately made that specific recovery possible. And there are doubtless many other reasons why different people place a high “value” on their various finds regardless of monetary considerations. Attached is a multi-photo of more modern coins and tokens to point out that none of these examples are worth more than a few dollars apiece, but yet these are some of my favorite finds. I couldn’t possibly part with them and it obviously has nothing to do with monetary value. They represent successes that resulted directly from my research efforts and fieldcraft. There is a feeling of accomplishment, and that is the primary “value” that matters most to me.................Jim. -

Detecting Shorelines & Being Prepared

Jim Hemmingway replied to Gerry in Idaho's topic in Minelab Metal Detectors

Hi Gerry… can’t doubt your determination after reading about this adventurous trip into the high country overlooking Lake Tahoe!!! I don’t know how you could brave water detecting in winter conditions without a wetsuit, but the scenery alone was certainly worth the visit. We can only imagine what a welcome surprise that picturesque area was to the first explorers and later settlers. As a longtime water hunter and outdoor enthusiast, I’ve also made decisions that resulted in late night travel in remote areas, sleeping in strange places, and pursuing cold weather detecting activities as per the photo below. That’s my prospecting camp in early October, not that unusual, but snow never stays that early in the season. So while unplanned changes on the road frequently lead to inconvenience, nonetheless I do admire your determination to follow your instincts and pursue your objectives. I first viewed your photos before reading the text of your post. Couldn’t help but notice the jug of Double Nut Brown Ale, it must look awfully good to a thirsty wayfarer!!! I use a similar looking jug for mixing frozen fruit juices, as illustrated below. A bit of a coincidence, so I took a photo just for the heck of it!!! Finally did read your article, an impromptu and enjoyable narrative. Congratulations on your recoveries, particularly that handsome gold ring. The silver dime shows some deterioration but to me a seated liberty is a beautiful piece of history in any condition. I also like the last photo of you standing in the snow, elevating your scoop and detector. You look content and happy to be in those environs, doing what you enjoy on your own terms. Many thanks for sharing the trip with us, and for the descriptive photos too!!! Jim. PS: Would have preferred to reply sooner, but my computer has usually been unable to either post to, or sign off this forum. The issue could be mine because it recently went in to the repair shop. No operating issues elsewhere to date. -

Help In Identifying This Rock

Jim Hemmingway replied to billdean's topic in Rocks, Minerals, Gems & Geology

Hi billdean… we’ve been finding naturally occurring native silver in northeastern Ontario for many years, but that experience doesn’t make it much easier to identify samples from other areas of the continent. That is because sample photographs are far less advantageous than having the actual sample in our hands to examine. That the rock responds to a PI metal detector is a pretty good indication of native metal, but not necessarily conclusive. There are a couple of sulfides and at least four of the more common arsenides in our area that do respond with perfectly good “metallic” signals to PI units. Incidentally arsenopyrite does not respond to my PI units. I suggest that you run a quick, simple streak test on the suspect material to confirm whether it is indeed native metal or for example a white or silvery sulfide, or possibly galena. Please determine the streak produced from one of the exposed occurrences in question. Select an area that protrudes from the surface. Rub it lightly across some white / beige porcelain tile or something similar from around the house that’ll give you a decent indication. For example, the bottoms of coffee mugs or French onion soup bowls are occasionally unglazed and will work just fine. Malleable silver produces a metallic silvery streak, whereas the brittle silvery sulfides generally produce dark streaks. None of them produce silver’s white metallic streak. There are other tests we can do to confirm silver, but the streak test is usually preferable because it is non-invasive. It won't damage your specimen. Below are two small naturally occurring native silver examples that were field cleaned prior to the photos. Both exhibit silver nodules or horns protruding from the rock surface, which is fairly characteristic of native silver in our area. Obviously a rock that has been subjected to the effects of erosion over eons of time will be characterized by a smooth or worn surface . But let’s hope the photos will be of some use to you as you examine your sample………………..Jim. -

What Is This? Bright Silver In Rock

Jim Hemmingway replied to Rods's topic in Rocks, Minerals, Gems & Geology

Hi Rods… welcome to the forum!!! Your rock presents an intriguing identification challenge for us because you’ve provided no information about it. For example, is there a mining history where it was found, did it respond to a metal detector, does the mineral feel weighty for its size / volume, is the shiny substance on your rock flexible or rigid? Or is what we see a result of light reflection as it pertains to the camera to sample angle. You see the real thing, we have to guess at what is real in the photo. Would you mind doing a simple streak test for us? It takes only about 10 seconds to do. The streak test involves lightly running the “shiny” substance on your rock across an unglazed white porcelain tile. In a pinch you can try rubbing your sample across the unglazed bottom surface of some coffee mugs or whatever is available around the house. With dark minerals, the color of the streak can be quite different from the mineral color, thus providing a very useful clue as to its identity. A streak test can readily eliminate a number of possibilities. Goethite produces a brown-yellow to yellow streak. Various forms of hematite can produce a range from a bright to quite a dark cherry red streak. Galena produces a black streak. Silver produces a silvery streak. And there are other possibilities, but there is no mistaking the difference in streak results between the minerals suggested above. Below are photos for the above suggested minerals. The goethite has a weathered surface, but look at the small exposed area of black lustrous material to see what actually exists beneath the surface. Note that galena has a distinct “grey” color and metallic luster. Specular hematite is a little more difficult because its uneven or crystallized surface makes it impossible to avoid light reflection from many faces. It is generally lustrous, but it is also primarily black. It can readily be distinguished from other similar-looking minerals such as ilmenite and magnetite by its red streak. Hopefully the photos will be of some use for you to compare to your sample. Let's add a molybdenite (a flexible mineral) photo just in case. But please consider doing the streak test and let us know the results if that is convenient for you……………….Jim. -

Hi Chris… it’s a subjective decision, but for whatever it’s worth I wouldn’t do any treatment to your sample. It displays well and is otherwise quite an attractive specimen in its current state. Dave hopefully can satisfactorily identify it for you shortly. It is not a simple task to identify your mineral based on a photograph. A black streak test result implies a mineral compound, and not strictly a native metal. Some non-metal minerals do react to both VLF and PI units, producing good metalliferous type signals. In northeastern Ontario, these include solidly structured pyrrhotite, niccolite, cobalt, safflorite, skutterudite, and quite a number of potential silver-cobalt-nickel-iron-arsenide mineral permutations that you will never encounter in generally circulated mineralogical texts. The silver mineral combinations are sufficiently complex and numerous as to require a reference list from the local museum, and more sophisticated identification techniques are required than the common mineral field tests normally available to hobbyists. We can easily imagine that such minerals would present insurmountable identification issues for hobbyists in the field and certainly the same applies in the context of forum discussion here. Many of these minerals freshly exposed would produce a similar appearance to the silvery material in your photo. But the primarily cobalt-nickel-iron-arsenide related minerals do not necessarily account for the black host material in your photo with any real confidence. And frankly, I have no idea if these mineral types potentially even exist in your search areas. There are other suggestions above, such as the enriched copper sulfides (bornite-covellite-chalcocite) that do produce VLF target signals, but do not react to my PI units. Unfortunately I’m not familiar with GPZ responses to various minerals because we have no hands-on experience with it to date. Attached are a few mineral examples mentioned in this thread including a photo of low-grade cuprite (it’s all I’ve got). Chris R. above makes a perfectly viable case for this mineral’s consideration. Thanks for an interesting topic, it’s been an enjoyable diversion to post our possible solutions for you!!!

-

Howdy Chuck… I’ve been metal detecting for coins, jewelry in freshwater knee-to-shoulder depths, prospecting for native silver and many other minerals, and digging old bottles for 32+ years. Our Ontario substrates range from moderate to high non-conductive ferromagnetic mineralizations. I’ve experimented with multi-frequency detectors in the past without any significant improvement in overall results at local coin hunting sites. That is not to suggest that more recent multi-frequency market releases might not be an improvement. Membership posts here certainly suggest, for example, that the Minelab Equinox represents a meaningful VLF technological advancement. Nearly all my coin and jewelry recoveries over the years have been detected with single frequency units that range from a 2.5 kHz Fisher Aquanaut to roughly 7kHz White’s coin hunting units. Both 13 / 14 kHz Fisher F75 / White’s MXT are employed for hunting naturally occurring native silver, particularly for trenching and close-up work. We also use both the White’s TDI Pro and Garrett’s Infinium PI for prospecting silver where conditions, for example the substrate’s magnetic susceptibility, and light trash density make these units equipped with larger coils more desirable tools compared to current VLF technology. We continue to enjoy good success primarily because we think about what we’re trying to achieve, do the necessary research to get results, and make the effort to get into the field. A good deal of our research is completed “hands-on” in the field. Aside from the frequently discussed search strategies we read about on the forums, for example achieving depth, covering ground and so on, a part of our success in coin hunting and prospecting native silver is that we do not employ detectors that are overly sensitive to small material. In such applications, tiny signals are a time-consuming distraction that subtract from our productivity in the field. How we employ metal detector technologies to satisfactorily accomplish a task is certainly of the utmost importance, but make no mistake that placing your coil over productive ground is by far and away the primary goal of experienced, consistently successful hobbyists. That means complying with basic research requirements first and foremost. It is hard work, particularly evaluating field sites for future reference, but without that information in hand, the fancy new technology has little or no value………………….Jim.

-

Hi Chris… that’s an attractive specimen you have there. It certainly looks like native silver. Have a look around the house for an unglazed white or beige porcelain type of surface. The unfinished bottoms of some types of soup bowls or coffee cups will suffice nicely for a simple streak test. Silver is soft, it reacts to metal detectors similar to native gold, and it produces a silvery streak. Galena with sufficiently solid structure will certainly react to VLF metal detectors and pinpointers such as my Garrett Propointer. But none of my large galena samples will react to a PI unit. Galena produces a soft wide black streak that cannot be misidentified as silver. The black mineralization adjacent to the silvery metal on your sample could also be comprised mostly of native silver with a black silver sulfide coating. That would help to explain the strong signal produced in the field. However, it could very well be a silver sulfide such as acanthite or perhaps even a dark silver sulfosalt. I can’t be more specific from a photo, although I'd put my money down on it being native silver embedded in acanthite. In any practical sense, related silver minerals such as acanthite do not react to metal detectors in the field.

-

Silver Sings! Happy New Years To All!

Jim Hemmingway replied to idahogold's topic in Detector Prospector Forum

Hello Idahogold… thanks for another enjoyable video. I find it interesting to observe others in the field, their techniques, reactions and interesting comments. Attached below is some small silver, plus an additional specimen found a few years ago in the north country. More about its recovery can be read on this forum at.... Thanks again Idaho ……………..............Jim. -

Hi Gerry… your boy grasping the pig is a great find, especially finished in brass. We even keep iron relics from prospecting country for future reference or use. Your recovery will make a fantastic mantelpiece and be quite a conversation piece over the years. WTG!!! I have not made any oddball finds in a few years, but depicted below is the last really different or unusual find that surfaced in the old Lion’s Club Park adjacent to an Anglican Church where we were married many years ago. It’s the only brooch I’ve ever found in thirty-two plus years of metal detecting. The soil was essentially a clay loam that became enriched with spruce and broadleaf detritus for well over a century such that it has evolved into quite a dark fertile substrate. I mention this factor because the silver brooch was at least six-to-seven inches deep, a fair indication that it has likely been in the ground for some sixty-to-seventy years and perhaps even more. It is infinitely exciting to dig down into the dark depths to find untarnished silver gleaming back at you. In fact there was no evidence of sulfide reduction on this piece, hence it was scrubbed with a toothbrush under warm tapwater and towel dried to what you see below. There are no markings on it, the target ID is in the lower silver quarter range, and looks to be about sterling quality. The stone may very well be colored glass, but then too it could be aquamarine. For obvious reasons I don't want to do a hardness test on it. Apparently aquamarine with silver is fairly common according to my wife. I don’t see aquamarine in our mineral collecting areas and really can't identify it with any confidence without utilizing a spectroscope. In this case it probably doesn't matter anyway. Many thanks for another interesting thread. It prompts us to actually think about our various recoveries and what we do with them after the hunt. My coin and jewelry finds normally get tossed into a container stored in the basement, never to be seen again unless my daughters or wife wish to have them. It’s the search with that magical metal detector that I so enjoy…………….Jim.